So, those wacky Iowa Republic caucus-goers, huh? My attitude is summed up in Jeff Maurer's headline. Welp: That Was the Worst-Case Scenario.

No excerpt, but recommended, if you have to laugh to keep from crying.

The NR editors opine on a lack of elephant spine: Republican Abandonment of Entitlement Reform Reckless. We all know about Trump and DeSantis. But:

To her credit, Haley is the one remaining candidate who has been consistent in arguing that the Social Security and Medicare programs are facing a crisis that needs to be addressed, warning that “we can’t put our head in the sand” by ignoring the problem.

The exact reforms she is proposing, however, would need fleshing out. In the debate, she said she would raise the retirement age, but only for those currently in their 20s — and she wouldn’t directly answer whether she would put the age at 70. Delaying the retirements of those who won’t be collecting benefits until 40 years from now won’t do much to move the needle. She also floated using a different measure of inflation to determine benefits and said she would limit benefits on higher-income individuals.

Even if Haley were to somehow pull off an upset in the primary and become president, it’s hard to see her having many takers among fellow Republicans, who would have to be united to overcome total resistance from Democrats to any changes.

Still, however unfleshed her proposals, that is the main reason I like her.

And, at the Federalist, Christopher Jacobs tells the truth about House Republicans: Johnson Cut His Bad Deal Because GOP Doesn’t Want To Cut Spending.

The outline of the spending agreement House Speaker Mike Johnson, R-La., cut with Democratic leaders sounds bad on its face. But the underlying reasons for that agreement seem far worse.

As I wrote last week, “Speaker Johnson and Republican ‘leadership’ … bailed the Democrats out of the predicament they put themselves in last May.” To which I should make an important addition: In many ways, Johnson didn’t bail out Democrats from a tough political predicament as much as he did his own Republican members. Because most Republicans don’t want to reduce spending — and they don’t want their constituents to know that either.

So in sum: the Republicans are poising to renominate a bloviating bullshitter who's advocating a $300 billion per year tax hike. The Democrats would be out of the question even if their candidate wasn't demented. And the Libertarian Party looks like it will be holding its nominating convention in Crazy Clown City.

Ah well. It's not as if my vote counted.

Also of note:

-

In case you had heard otherwise… Noah Smith takes a cudgel to an undeservedly common notion: Nations don't get rich by plundering other nations. One of the tweets he offers as typical:

Where did America’s wealth come from if not from plundering South America and then the rest of world?

— Khayyam 🇵🇸 (@kkhayyam1) December 16, 2023He counters:

This idea is a pillar of “third world” socialism and “decolonial” thinking, but it also exists on the political Right. This is, in a sense, a very natural thing to believe — imperialism is a very real feature of world history, and natural resources sometimes do get looted. So this isn’t a straw man; it’s a common misconception that needs debunking. And it’s important to debunk it, because only when we understand how nations actually do get rich can we Americans make sure we take the necessary steps to make sure our nation stays rich. (There actually are some more sophisticated academic ideas along similar lines, and I’ll talk about those in a bit.)

So anyway, on to the debunk. The first thing to notice is that in the past, no country was rich. There’s lots of uncertainty involved in historical GDP data — plenty we don’t actually know about populations, prices, and what people consumed in those eras. But even allowing for quite a bit of uncertainty, it’s definitely true that the average citizen of a developed country, or a middle-income country, is far more materially wealthy than their ancestors were 200 years ago:

It's sounds as if it could be a "correlation doesn't imply causation" fallacy, but Smith shows that even the evidence for correlation isn't there.

-

States don't get rich by plundering their citizenry either. Andrew Cline of the Josiah Bartlett Center wonders: Will New Hampshire's income tax finally die this year?. Fingers crossed, right? But:

New Hampshire is less than a year away from eliminating its income tax.

Maybe.

A bill up for consideration in the House Ways & Means Committee on Tuesday would bring it back.

It’s a myth that New Hampshire has no income tax. The state’s Interest & Dividends Tax is a levy on income derived from dividends or interest. Under current law, this tax expires on Dec. 31 of this year. That would make New Hampshire the eighth U.S. state with no direct tax on personal income.

Joining that elite club won’t happen if the Legislature endorses a plan by state Reps. Susan Almy and Mary Jane Wallner. Their House Bill 1492 would bring the income tax back from the dead.

As usual with Democrat proposals, it's aimed at "the rich". By which they mean: anyone who's (ahem) got a decent-sized nest egg at an investment company or bank.

-

Love Hertz? Allysia Finley writes at the WSJ on Hertz, Tesla and the Perils of CEO Groupthink. After relating Hertz's big bet on an electric vehicle future…

The market has changed. Electric-vehicle euphoria has crashed into reality, and Hertz’s bet has gone south. On Jan. 11 the rental-car giant announced it would sell roughly a third of its global EV fleet and use the proceeds to buy gasoline-powered cars. The cited reasons: weak demand for EVs and high repair costs.

Readers might have heard that lower maintenance costs are a major electric-vehicle advantage. As Hertz discovered, the opposite it true. Even minor accidents can require batteries to be replaced, which can cost $20,000. Many EV parts aren’t readily available, so cars have to sit in the shop for weeks.

Ms Finley notes that similar missteps, efforts to please "stakeholders" instead of shareholders, have plagued Coca-Cola and Delta. We could add Disney, Unilever, ‥

-

TANSTAAFL watch. Kevin D. Williamson wonders: What If There Is No Low-Hanging Economic Fruit?

Joe Biden is in an economic-political bind, partly of his own making and partly more than a century in the making: He is a hostage of our national religion, the cult of the magic president.

In this case, it is the president-as-rainmaker, the guy who is responsible for the economy—a belief founded on very little other than pure superstition rooted in ancient magical beliefs about national/tribal leaders as intercessors between men and the gods, who by their personal virtue and ceremonial correctness ensure material prosperity. If the rains are timely and the crops abundant, then the king has done right. If there is disease or drought, then …

In the (very) old days, a sacral king who lost the mandate of heaven might expect to be ritually murdered by his successor, but now we just have elections—unless you take Donald Trump’s lawyers seriously, in which case apparently we can expect doddering incumbents to murder their would-be successors. As a tradition-minded conservative, I have to say that I prefer it the other way around, but that’s a longer story.

For the record, I do not favor the ritual murder of Joe Biden.

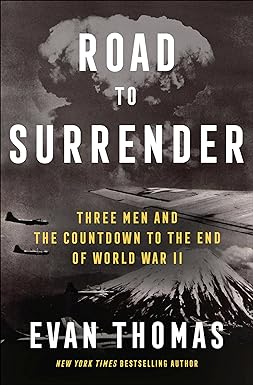

| Recently on the book blog: |

![[The Blogger and His Dog]](/ps/images/me_with_barney.jpg)