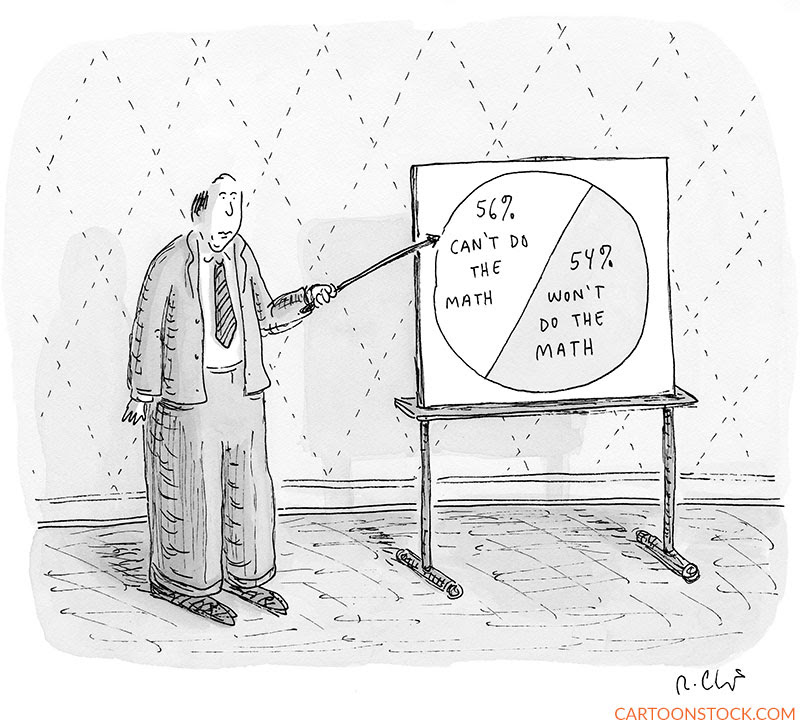

At the Josiah Bartlett Center, Drew Cline channels his inner Monty Python: Legislators distributing random numbers is no basis for sound public policy.

Random chance is a constant feature of life on Earth, and for centuries it was a feature of human government. Kings and councils ruled with “arbitrary power,” as John Locke phrased it, subjecting the people to the whims of man just as they had previously been subject to the whims of nature.

Escaping the tyranny of randomness was, to Locke and the American Founders, a primary motivating factor of those who built republican governments.

“This freedom from absolute, arbitrary power, is so necessary to, and closely joined with a man’s preservation, that he cannot part with it, but by what forfeits his preservation and life together,” Locke wrote in the Second Treatise on Government.

By “absolute power,” Locke meant rule by whim, not by law. But the Founders feared that in a republican government majorities would write laws that codified their whims and impulses rather than the considered opinions of a broader coalition of lawmakers. Hamilton and Madison were particularly animated in warning against this.

Drew provides examples from legislation proposed in our state legislature. To me, it brought to mind a Reason article from Eric Boehm last month: If Semiconductor Chip Demand Is High, Why Do We Need More Subsidies? Which starts:

The Biden administration has yet to announce how it plans to spend the $52 billion in semiconductor manufacturing subsidies that Congress approved more than 18 months ago.

You would think a rational way for government to spend taxpayer dollars would be to total up the costs of the things that needed to be done to achieve specific goals. Then, ask for that much money.

It's pretty clear that's not what happened here; the Biden Administration demanded a big chunk of money first. Our dumbshit Congress said "Here ya go, Joe!". And only now is the Administration trying to figure out what to do with that essentially random number, arrived at by whim.

Also of note:

-

So long, Hong Kong. Liz Wolfe has some sad news about recent legislation passed in a once-free polity: Hong Kong Falls, Again.

At China's behest: Yesterday, Hong Kong passed a new national security law that will create draconian penalties for all manner of political crimes. Beijing puppet/Hong Kong leader John Lee says these swiftly passed laws "allow Hong Kong to effectively prevent and put a stop to espionage activities, the conspiracies and traps of intelligence units and the infiltration and damage of enemy forces." He's trying to push a narrative that such laws—passed expeditiously over 11 days, the fastest a bill has gone through Hong Kong's legislature since 1997—are needed to thwart Western spying. But what they actually represent is a massive encroachment on the already-eroded civil liberties of Hongkongers who have been absorbed back under mainland Chinese rule.

Liberty: fun while it lasted.

-

I didn't expect anything else, did you? Jeff Jacoby looks at the lastest from the senator from the state to our immediate west: Sanders's foreign policy 'revolution' is a string of leftist clichés.

THIS WEEK Foreign Affairs published a 2,800-word essay by Bernie Sanders, the US senator from Vermont whose campaigns for president in 2016 and 2020, though unsuccessful, attracted wide interest and support. Sanders calls himself a democratic socialist and his essay, titled "A Revolution in American Foreign Policy," faithfully reflects the far-left worldview he has always embraced.

That worldview is easily summarized: Most of what is bad in world affairs can be blamed on the United States, and especially on American corporations and billionaires. Like the radical scholars Noam Chomsky and the late Howard Zinn, Sanders sees US foreign policy as fundamentally "disastrous," a word he uses repeatedly in his essay. "For many decades, there has been a 'bipartisan consensus' on foreign affairs," Sanders writes in his opening paragraph. "Tragically, that consensus has almost always been wrong."

Fun fact: Bernie won the New Hampshire primary a mere four years ago.

-

Speaking of things politicians get wrong… Veronique de Rugy applies a new term to old behavior: Industrial Policy and Protectionism Are Luxury Beliefs for the New Right.

If you've heard of the concept of "luxury beliefs," you can thank writer Rob Henderson. Henderson's concept refers to cultural and political ideas that are predominantly held and advertised by individuals in society's upper echelons—those persons with significant economic, social, and cultural capital—to demonstrate that they are on the side of the downtrodden, minorities, and the poor.

Henderson's new memoir, Troubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social Class, discusses luxury beliefs, a concept he developed during his time at Yale. Henderson had a difficult childhood spent in foster care, and he felt distanced from his Ivy League contemporaries, who espoused fashionable but unworkable or outright harmful views that they themselves were insulated from by some combination of status, wealth, and familial stability. The luxury beliefs Henderson witnessed were a way to signal and maintain elite status by supporting social concepts or policies that sounded empathetic. Yet in reality, they made life worse for those at the bottom rungs of society.

Henderson argues that luxury beliefs are not just harmless opinions. They can have negative real-world implications, influencing policy and societal norms in ways that might exacerbate inequality or disconnect the elite from the broader societal consequences of the positions that they advocate.

Another way to look at it: people advocating policies when they have absolutely zero skin in the game, no risk whatsoever that implementing their ideas will come back to bite them in the ass. Also see: Chuck Schumer on Israel.

| Recently on the book blog: |

![[The Blogger and His Dog]](/ps/images/me_with_barney.jpg)