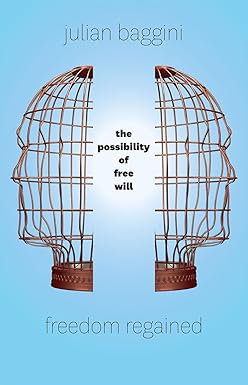

The author, Julian Baggini, is (I think it's fair to say) a pop philosopher. A serious thinker combined with a considerable amount of self-promotion. ("Not that there's anything wrong with that," said the blogger.) I became aware of this book when I looked back at his WSJ review of Science and the Good, which dealt tangentially with the issue of "free will." I've been a longtime fan of that topic.

I was very impressed with Baggini's approach to "free will": he's not so much arguing for a position for or against, but outlining his earnest search for the truth behind the topic. Perhaps unique for a book of this type, Baggini goes out and interviews other philosophers and researchers. Also artists and addicts. He fairly presents their views and insights. For a relatively short book, it's a real tour de force. His writing style is clear and mostly accessible to even a philosophical dilettante like me.

Baggini urges the reader to avoid the trap of thinking of "free will" as a binary, all-or-nothing deal, where we are either (a) completely deterministic bags of molecules, perhaps with some quantum coin-flipping going on; or (b) completely in control of our actions with the ability to choose any future path at any moment.

The truth, argues Baggini, is somewhere in between, depends on our situations, values, and past histories. Which makes things a little messy, but manageable. For this (very bad) Lutheran, his deployment of Martin Luther's famous quote "Here I stand, I can do no other" was very on-target.

Baggini's exploration takes him to various free will-related topics, some surprising: artistic expression, legal responsibility, addiction, mental illness, and more.

Not that I'm in total agreement. Almost as an aside, Baggini claims "Freedom merely as absence of constraint and presence of consumer choice is a very thin value indeed". Whereas I think, given its relative rarity and fragility, it's actually a pretty good deal, and not a "very thin value" at all.

Baggini's also read Free Will, by anti-free willer Sam Harris. Interestingly, he quotes the same bit of the text that I did back in 2015, where Harris is musing about Joshua Komisarjevsky, participant in a 2007 Connecticut rape-murder. Harris makes the (to me) sloppy, albeit astounding, claim:

If I had truly been in Komisarjevsky's shoes on July 23, 2007—that is, if I had his genes and life experience and an identical brain (or soul) in an identical state—I would have acted exactly as he did.

Baggini lets this go largely unremarked, but I thought back then (and still do) that there's a real problem with "I" in Harris's sentence. Given Komisarjevsky's brain, genes, experience, etc.: there's no room for Harris's "I" to squeeze in.

At the end, Baggini comes close to making a fully-libertarian argument. But then backs off considerably with (to me) weak hand-waving about the justified role of the state in providing health care, education, transportation infrastructure. Ah well.

I realize that I'm coming close to complaining that Baggini didn't write the book the way I would have. So don't get me wrong: if you're interested in "free will", this is a very good book to check out.

![[The Blogger]](/ps/images/barred.jpg)