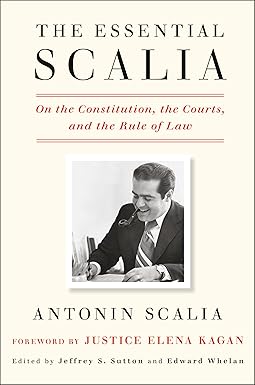

Based on Bryan Garner's column in a recent issue of National Review, I was gonna check out the book he wrote with Antonin Scalia, Reading Law: The Interpretation of Legal Texts. But when I picked that up off a shelf of the Portsmouth (NH) Public Library, I quickly discovered it was a very dense reference work aimed at lawyers. So I checked out this one instead, an unusual choice for me, but a pretty good one.

I don't often quote book cover blurbs, but this one has an excerpt from SCOTUS Justice Elena Kagan's lovely foreword:

I envy the reader who has picked up this book, as I once picked up [Nino's] opinions, not knowing what he or she will find … In these last few years, I have missed the enjoyment and excitement — even the exasperation — that came from thinking about Nino's latest opinion. I doubt that anyone who turns the final page of this book will wonder why. No one has ever written quite like Nino, and no one ever will … So … learn from the contents of this book. And equally, challenge the contents of this book. (Nino would have wanted you to.) But above all else, enjoy them.

I do not dissent from Kagan's opinion.

The book is a compendium of Scalia's SCOTUS opinions (including dissents), as well as some articles and lectures he gave over the years. It's a great overview of a fine legal mind, who also happened to have a knack for a well-turned phrase. There are no howlers, but his prose is full of sly wit that made me smile. (And, rarely, he will be obviously annoyed with the other side in his dissents, and the resulting zingers are pretty good too.)

I was somewhat surprised at the occasional makeup of the justices concurring with Scalia's opinions. I had not appreciated his strict views on criminal protections. For example, his decision about thermal-imaging a pot grower's house without a warrant, Kyllo vs. United States, was joined by David Souter, Clarence Thomas, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and Stephen Breyer. Not the usual lineup.

A final section of the book deals with "administrative law", the regulations promulgated by executive agencies powered by handoffs from Congress. It opens with a 1989 speech, where his first line is "Administrative law is not for sissies." I admit, just about all of the argument in this section flew over my head, so I definitely count myself as a sissy here. Apparently, Scalia's views on "Chevron deference"—a doctrine which SCOTUS "overturned" last year—evolved over time. But I only got a vague notion of the issues involved.

![[The Blogger]](/ps/images/barred.jpg)