Near the end of this book, the biographer, Jennifer Burns, mentions a couple of quotes from our current President. One from 2020:

"Milton Friedman isn’t running the show anymore."

No fooling. And one from 2019:

"When did Milton Friedman die and become king?"Milton Friedman died in 2006, Joe. (Even back then, Biden sounded like one of the geezers in the Saturday Night Live parody ad for the Amazon Echo Silver.)

So Friedman has been haunting Joe's brain ("rent free" as they say), probably for a long time. In contrast, I've been a fan ever since I read his Capitalism and Freedom as an impressionable youngster back in the 1960s. I honored his passing in my blog here and here. Key quote from the former link: "As one of the foremost champions of liberty and capitalism, Dr. Friedman undoubtedly made life better for you, me, and posterity." (Caveat lector: Unfortunately, many of the links I gathered from 2006 no longer work.)

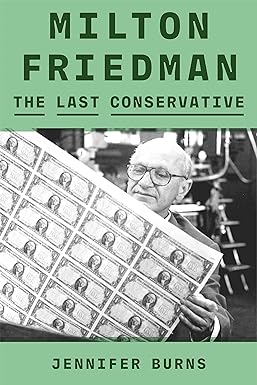

This book garnered many laudatory reviews when it came out last year, so I snagged it from the New Books table at Portsmouth Public Library. (Yes, even in a socialist library in one of the state's wokest cities, you can still get fair-minded books about conservative/libertarian subjects.) And, yes, I agree: it's quite good. Burns is (it says on the back flap) a Stanford history professor, but she's clearly absorbed a lot of economics along the way: her discussion shows a deep understanding of the concepts and controversies associated with Friedman's work. The book seems to be almost as much about US economic history from 1930 to the present day as it is about Milton. (With side trips to Chile and Great Britain.)

I smiled at an anecdote about Friedman's undergrad days at Rutgers: "In his first year, he found a job waiting tables, which came with a supposedly free lunch. Even then, he was enough of a budding economist to understand there was no such thing-the free lunch came at the expense of a higher wage."

And there's a romantic-comedy-for-econ-geeks anecdote about Milton's meet-cute with his wife-to-be, Rose: she was a classmate in a University of Chicago course taught by a tyrannical professor. One day the prof botched differentiating a function, and Milton bravely pointed out the error. The prof blustered, Milton held his ground, and Rose was impressed enough to invite Milton to a Frank Knight lecture.

Burns does an excellent job charting Friedman's odyssey from the lonely days when his free-market monetarist views were dismissed by "serious" economists to his gradual ascension to respectability (including, of course, the Nobel).

About the only irritation I found was Burns' criticism of Friedman for his opposition to some of the more coercive features of 1960s civil rights legislation. She shows little patience for Friedman's devotion to classical liberal principle: people should feel free to engage (or not to engage) in voluntary, mutually beneficial economic transactions. Burns, to my eye, gets a little vitriolic when attacking that view.

![[The Blogger and His Dog]](/ps/images/me_with_barney.jpg)